Saturday, May 3, 2014

How the 1960s Influenced EDM Music

Here is a link to my Extra Credit Presentation and the list of sources:

http://screencast-o-matic.com/watch/c2heilnx6l

Sources:

1. Goodwin, Susan and Becky Bradley. "1960-1969." American Cultural History. Lone Star College-Kingwood Library. Last modified July 2010.http://wwwappskc.lonestar.edu/popculture/decade60.html.

2. Don Lattin, The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for America (New York: HarperOne, 2011)

Monday, April 28, 2014

The Dawn of The Millennials

The 21st

century in the United States shows that culture is constantly changing and the

change is influenced by previous decades. While reading Eddie Huang’s story in

his memoir Fresh Off the Boat, I noticed many similarities between

American cultures in the 21st century and the other decades we

learned in this course. The attitude today toward immigration, religion,

politics, economics, and education are all influenced by previous decades.

Immigration in

relation to economics is probably the main topic in Fresh Off the Boat.

I saw a parallel between the immigration era of the Gilded Age and in the last

decades of the 20th century. During the Gilded Age, America

experienced an era of rapid economic growth as American wages became much

higher than in Europe. Because of the economic opportunities in rapid

industrialized, urbanized, and thriving cities, America encountered a “stream

of immigration… more arrived everyday.”[1]

In the late 20th century and beginning of the 21st

century, the United States experienced a similar trend in immigration as the

Gilded Age. During the last decade of the 20th century after the

collapse of Eastern European Communism and the Soviet Union, the United States

became the world’s sole superpower. During this time, The United states

possessed the world’s most productive economy. The country also dominated

global trade and banking, and the economy grew rapidly due to a sharp fall in

interest rates, price of oil, and the growth of the new computer technologies.[2] Because

of this thriving trend in economics, the Huang family along with many other

families left their homes and came to America. In the memoir, Eddie explained,

“Mom made sure I was aware of money and how important it is… if you asked her

why we came to America, she’d tell you straight up: cold hard cash.”[3] A

solid example of this would be when Eddie’s father went to Orlando to pursue

the restaurant business. Like Chicago for the Everleigh sisters, the Huangs

knew “the rush was real in the those cities…enabled and empowered by new

money.”[4]

Immigration in

relation to economics is probably the main topic in Fresh Off the Boat.

I saw a parallel between the immigration era of the Gilded Age and in the last

decades of the 20th century. During the Gilded Age, America

experienced an era of rapid economic growth as American wages became much

higher than in Europe. Because of the economic opportunities in rapid

industrialized, urbanized, and thriving cities, America encountered a “stream

of immigration… more arrived everyday.”[1]

In the late 20th century and beginning of the 21st

century, the United States experienced a similar trend in immigration as the

Gilded Age. During the last decade of the 20th century after the

collapse of Eastern European Communism and the Soviet Union, the United States

became the world’s sole superpower. During this time, The United states

possessed the world’s most productive economy. The country also dominated

global trade and banking, and the economy grew rapidly due to a sharp fall in

interest rates, price of oil, and the growth of the new computer technologies.[2] Because

of this thriving trend in economics, the Huang family along with many other

families left their homes and came to America. In the memoir, Eddie explained,

“Mom made sure I was aware of money and how important it is… if you asked her

why we came to America, she’d tell you straight up: cold hard cash.”[3] A

solid example of this would be when Eddie’s father went to Orlando to pursue

the restaurant business. Like Chicago for the Everleigh sisters, the Huangs

knew “the rush was real in the those cities…enabled and empowered by new

money.”[4] |

| Eddie Huang (circled) and his family |

The revolutionary

ways of thinking in the 1960s, which created the dramatic change in American

culture and more specifically in education, had a lasting impact. In the 1960s,

college students began to use education to stimulate and form their own ideals,

and the traditional sense of a college education began to disintegrate. The attitude was set by figures like

Andy Weil where “Andy was reluctant to go with the flow…he could see that

having any more of the insights might convince him Harvard was a waste of

time”.[5] This

attitude among college students clearly stuck and now demonstrations of

political activism, anti-war movements, and civil rights movements is a big

part of the culture on college campuses. When Eddie and his friends were denied

the opportunity to debate about the legalization of marijuana in college, he

expressed, “we gave up on doing it their way, we wanted to get free.”[6]

Eventually, Eddie left his first college, but unlike many of the young

college-age men and women in the 1960s who simply just “dropped out”, Eddie

still sought after a degree. Unlike previous decades, today, a college education

is more of a necessity. Since the recession, jobs became scarcer and most employers

will only hire college graduates with degrees. Thus, American universities

began to see a boom in applicants in the past decade.

Even though I am a decade younger than

Eddie, most things seemed to have remained the same. For example in politics, the main issues that divided the

US political landscape when Eddie grew up are the same issues that continue to

divide this country today. Some of the main ones are global warming, gun

control, music file sharing, drug sentencing guidelines, abortion, the recession,

and “the war on terror”[7].

Another example would be the Internet, which revolutionized how we live our

lives. An example from Fresh off the Boat

is when Karmaloop, an online retail store, “had more buying power than any

physical store.”[8]

Americans began relying on the Internet for shopping, information, and

communication, and still continues today.

Even though I am a decade younger than

Eddie, most things seemed to have remained the same. For example in politics, the main issues that divided the

US political landscape when Eddie grew up are the same issues that continue to

divide this country today. Some of the main ones are global warming, gun

control, music file sharing, drug sentencing guidelines, abortion, the recession,

and “the war on terror”[7].

Another example would be the Internet, which revolutionized how we live our

lives. An example from Fresh off the Boat

is when Karmaloop, an online retail store, “had more buying power than any

physical store.”[8]

Americans began relying on the Internet for shopping, information, and

communication, and still continues today.

[1]

Karen Abbot, Sin in the Second City: Madams,

Ministers, Playboys and the Battle for America's Soul (New York:

Random House, 2007), Prologue xxiii.

[2] S. Mintz, and S. McNeal.

Digital History, " Overview of the 1970-2000 Era." Accessed April 28,

2014. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=19&smtid=1.

[5]

Don Lattin, The Harvard

Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil

Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for America (New

York: HarperOne, 2011), 59.

[8]

Huang. Fresh off the

Boat, 230.

Friday, April 18, 2014

"Look Within, Do Your Own Thing"

The 1960s was the age of youth, a period when long-held

values and norms of behavior seemed to break down when the 70 million children

from the post-war baby boom became teenagers.[1]

The decade resulted in revolutionary ways of thinking that created dramatic

change in American culture. The changes affected education, values, lifestyles,

laws, entertainment, and attitudes toward sexuality.

The 1960s was the age of youth, a period when long-held

values and norms of behavior seemed to break down when the 70 million children

from the post-war baby boom became teenagers.[1]

The decade resulted in revolutionary ways of thinking that created dramatic

change in American culture. The changes affected education, values, lifestyles,

laws, entertainment, and attitudes toward sexuality.

The 1950s, a decade that would become synonymous with

unquestioning conformity, had seen the rise of the other-directed character-all

those middle class, upwardly mobile businessmen and consumers who focused on

other people’s opinion on them. By the early 1960s, however, more and more

Americans were starting to follow an inner voice. There was a new kind of

empathic individualism, a nonconformist mentality that would soon see full

flowering in the psychedelic drug culture.[2]

This trend is similar to the 1920s; a time of dramatic changes characterized by

prosperity, new ideas, and personal freedom caused profound social change and

cultural conflict that created “The Flapper”.[3]

But instead of being categorized as the roaring 20s with skin-clad flappers,

the 60s is categorized as the age of counterculture with bell-bottom, long hair

wearing hippies.

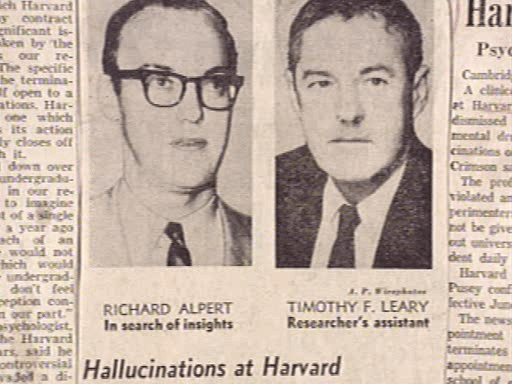

Representatives like Weil and Huston Smith found inspiration in works like John Dewy, an education reformer who developed “naturalistic theism”, which sought to reconcile religion in the scientific worldview and British writer Gerald Heard who claimed “evolution was not over, humanity was on the cusp of a breakthrough in consciousness”[4] These ideals led to the reform of mainly religion, politics, and education. The new view on religion is less organized and people were encouraged to “look within, find god within yourself…do your own thing”.[5] Politics became a topic of debate where hippies like Leary formed thoughts of “you could destroy both capitalism and socialism in one month with that sort of thing”.[6] However, education underwent the most change.

The young college-age men and women “dropped out” to separate

themselves from the conventional college education, for example, Andrew Weil. “Andy

was reluctant to go with the flow…he could see that having any more of the

insights might convince him Harvard was a waste of time”.[7]

College students began to think the education they obtained was not stimulating

enough and began forming their own ideals. Thus, many

college‐age men and women became political activists and

were the driving force behind the civil rights and antiwar movements.

For example, Berkeley

in 1964 to cover the free speech movement-the campus protests at the university

of California that kicked off a decade of unrest at schools across the nation.[8]

The counterculture ideas of the 1960s exhibited behaviors that

went against the norms of behavior, and psychedelic drugs were certainly a

factor that caused the manifestation of these ideals. “The idea was to

create a transcendental community whose members would fully experience life and

go beyond ego trips and social games”.[9]

After Leary discovered psychedelic mushrooms which the Aztecs called “the flesh

of the gods”,[10] and

claimed, “I learned more about psychology from these mushrooms than I did in

graduate school. These drugs can revolutionize the way we conceptualize

ourselves”.[11]

The drugs perpetuated a change in social arrangements as well. For example,

“The unorthodox scene inside the Kenwood Ave home…was an early warning sign of

a counterculture movement that would soon sweep across the nation… sexual

roles, living arrangements, and family structures were about to undergo rapid

revolutionary changes”.[12]

But what is most interesting is that Leary, Weil, Smith, and

others were genuinely trying to use psychedelic drugs to help society, which

sounds ridiculous to us because these drugs are seen as extremely harmful

today. But back then, these scholars who experimented with these drugs at

Harvard University believed “this could be of great benefit to society, curing

people of alcoholism or helping reduce the recidivism rate among criminals”.[13]

The research at the time looked promising and was even used to help alcoholics;

“it was the research that briefly brought bill Wilson, a cofounder of

alcoholics anonymous into the early psychedelic scene”.[14]

In my opinion, perhaps the biggest downfall of Leary, Weil

and Smith’s mission is mass media. At this time, most homes had television and

the news platforms were trusted for accurate news. The media brought to light

the problems surrounding psychedelic drugs by reporting headlines like “the

drugs has grown an alarming problem at UCLA and UC Berkeley... hundreds were

showing up in hospital emergency rooms, suffering from panic attacks and

psychotic reactions”, and also “young runaways from across the country was

victimized by a variety of sexual and chemical predators”.[15]

By the time Nixon announced that Leary was “the most dangerous man in America”[16]

during his war on drugs campaign, the public support toward the benefits of

psychedelic drugs began to shift.

|

| protester in 1960 |

|

| Protester Today |

I think the most prevalent similarity between the 1960s to today would be the debate on drugs specifically the legalization of marijuana. In the 60s marijuana was “seen at the time as the dangerous drug everyone was suppose to worry about”[17] but now some scientists and scholars are trying to push the potential health benefits of marijuana. It is interesting how the most dangerous drug of the 60s is now a big topic of debate that the mass media is narrating. Is the 1960s counterculture making its comeback? It certainly seems like it with the popularity of yoga, which was introduced when “Smith stood alongside a desk and chalkboard, writing mysterious words like yoga”.[18] Also, Leary’s idea that “you could destroy both capitalism and socialism in one month with that sort of thing”. [19] Seem to be the platform for many young protestors at events like Occupy Wall Street.

[1] Goodwin, Susan and Becky Bradley.

"1960-1969." American

Cultural History. Lone Star College-Kingwood Library. Last modified July 2010.

http://wwwappskc.lonestar.edu/popculture/decade60.html.

[2] Don Lattin, The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston

Smith, and Andrew Weil Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for

America (New York: HarperOne, 2011), 26.

[3] Joshua Zeitz, Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style,

Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern, (New York: Three Rivers

Press).

[5] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 105.

[6] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 110.

[8] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 86.

[9] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 104.

[10] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 38.

[11] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 52.

[12] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 101.

[13] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 115.

[14] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 66.

[15] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 143.

[16] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 60.

[17] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 92.

[18] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 35.

[19] Lattin,The Harvard

Psychedelic Club, 110.

Tuesday, April 8, 2014

The Dawn of a New Age: The Roaring 20s

The 1920s were a time of dramatic

changes characterized by prosperity, new ideas, and personal freedom that

caused profound social change and cultural conflict. Known as the “roaring

twenties” Americans reacted to the depression of World War I, and the culture

became somewhat of a giant party with the rise of consumer culture, the incline

of mass entertainment. America’s

population began shifting from rural areas to more urban ones and the growing

affordability of the automobile made people more mobile than ever. Although the

decade was known as the era of “revolution in morals and manners”[1], under the

surface conservative values still flourished as the nation saw the revival of

the Ku Klux Klan, the end of its open immigration policy, and the controversy

over evolution. The economic boom of the era was short lived, but the social

changes were lasting.

America’s cultural change is most

apparent in the prescience of The Flapper. During this time, “growing up in an

urban environment that afforded Americans opportunities for anonymity and

leisure, born in the era of mass reproduction, the flapper experimented openly

with sex and with style”.[2]

The Flapper’s actions directly defied the rules of her mother’s Victorian

generation. Victorians were appalled by their daughter’s lack of restraint,

daughters like Zelda Sayre. Zelda was the perfect example of a Flapper. She was

“commonly acknowledged as something of a wild child”[3]

as she would boldly assert her right to dance, drink, smoke, date, and

“habitually rouged her cheeks and stenciled her eyes with mascara, giving her

friends’ parents great cause for concern”.[4]

Sexual mores, gender roles, hairstyles, and dress all changed profoundly in the

1920s due to the Flapper. Millions of girls wanted to be Zelda, it was the age

of the Flapper.

The Flapper did not appear out of

think air, she was a product. “She belonged to the first

generations of Americans who were raised on advertisements and amusements

rather than religion and restraint”.[5]

There were many new amusements that were to blame for this cultural change.

First, there was jazz music where the new generation was thought to be “spoiled

by jazz music”[6] and dance halls.

Second, it was new innovations in technology when “the first sign of trouble

came when Americans fell in love with the bicycle” in the 1890s.[7]

Technological innovation became more and more advanced with first the telephone,

which came into wider use in the first decades of the new century and second

came the automobile. The mass production of automobiles and telephones caused

the end of the Victorian Era’s courtship system and culture as more and more

young adults obtained freedom.

Freedom is not only perpetuated by

technological advancements and mobility but also from urbanization and economic

forces. Many young women flooded to cities for employment where they were free

from the surveillance of their Victorian parents. For the first time ever, more

than 50 percent of Americans lived in cities than in the countryside. The mass

entry of women into the workforce due to industrialization and urbanization

meant, “Real money could buy real freedom”.[8]

This then caused for a demand of entertainment and leisure activities for the

newly freed young adults. Places like movie theaters and amusement parts like

Coney Island became big attractions for social gathering. This then meant, “The

apostles of good living were no longer ministers and schoolmasters, but advertising

executives who saturated American Newspapers, magazines, movie theaters, and

radio stations with a new gospel of indulgence”.[9]

The advertisements of this new leisure culture, as perpetuated by the new era

couple Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, meant men and women were ushered in a

culture where sex became more prominent.

Even though there were a lot of

liberal changes in the twenties, many felt insecure about these [10]

The Klan were known to “ruthlessly patrolled back roads in search of teenagers

embroiled in wild petting parties or improper embraces… flogged errant husbands

and wives, and tarred and feathered drunks”.[11]

Although the Klan’s actions were extreme, they represented the fair amount of

Americans that did not accept the cultural revolution of the 1920s. But is even

more interesting is that the 1920s flapper got the most criticism not from

Christian moralists or spokesmen for the older generation, not from politically

conservative men, but from feminists. To them, the New Women like Lois Long and

Zelda, struck many veteran feminists as apolitical who are only interested in

romantic and sexual frivolities and not “important issues like suffrage,

occupational health and safety, income equality, and legal rights”. To many the

new culture was “misguided at best”.[12]

Even though there were a lot of

liberal changes in the twenties, many felt insecure about these [10]

The Klan were known to “ruthlessly patrolled back roads in search of teenagers

embroiled in wild petting parties or improper embraces… flogged errant husbands

and wives, and tarred and feathered drunks”.[11]

Although the Klan’s actions were extreme, they represented the fair amount of

Americans that did not accept the cultural revolution of the 1920s. But is even

more interesting is that the 1920s flapper got the most criticism not from

Christian moralists or spokesmen for the older generation, not from politically

conservative men, but from feminists. To them, the New Women like Lois Long and

Zelda, struck many veteran feminists as apolitical who are only interested in

romantic and sexual frivolities and not “important issues like suffrage,

occupational health and safety, income equality, and legal rights”. To many the

new culture was “misguided at best”.[12] |

| Lois Long at Work |

The social changes brought by the

1920s did not disappear. I can see many similarities between the culture then

and now in our generation. For example, a survey of a high school students in

the 1920s revealed the five most frequent sources of disagreement between

teenagers and their parents which were “the number of times you go out on

school nights during the week, the hour you get in at night, grades at school,

your spending money, and the use of the automobile”.[13]

If the same survey were conducted today, the results would be the same. I know

those were some of the issues my parents and I fought over in high school. Also,

characters similar to Lois Long are still prevalent today. In the 1920s, Lois

Long was hired by The New Yorker to

write a regular column on New York nightlife. “Essentially, Long would be the

magazine’s resident flapper journalist… she continued her long nights of

drinking, dining, and dancing and regaled her captive readers with weekly tales

of her adventures on the town”.[14]

Lois Long’s career is identical to that of 21st century icon Carrie

Bradshaw, a character on the hit series “Sex and the City”. Carrie also had a

hit weekly column for a newspaper where she wrote about her and her best

girlfriend’s adventures of sex, dating, society, and all New York has to offer.

People might not be familiar with the name Lois Long, but they will certainly

know Carrie Bradshaw. And finally, lets not forget about the emergence of “the

celebrity”. In the 1920s, the Fitzgeralds came to age in a country that was

increasingly in the thrall of celebrity where sensational murder trials, sports

legends, and movie stars. Today, “the celebrity” like Brad and Angelina Jolie

enjoy similar coverage as that of the Fitzgeralds.

Lois Long said about the roaring

20s: “Tomorrow we may die, so let’s get drunk and make love”. Today, we like to

paraphrase this idea with the popular saying: “You Only Live Once - that’s the

motto YOLO”.

Tuesday, April 1, 2014

Lets get Progressive!

|

| Panorama of Chicago,1906 |

“Imagine yourself,”

Bell wrote about Chicago during the Progressive Era, “the screeching of

dope-filled and half drunken women; the throngs of young men going like mad

into these house of horror, where the air is reeking with the fumes of dope and

tobacco and millions of germs.”[1]

Can you imagine living in a place like this? The reformers of the Progressive

Era sure couldn’t and they were willing to do anything to get rid of such an

infectious place.

Parts

two and three of Sin in the

Second City, delved deep into the Progressive era when a wide range of

economic, political, social, and moral reforms took place. In the Progressive

era, there were efforts to outlaw just about anything that could be considered

detrimental to society like the sale of alcohol, regulating child labor,

restricting immigration, and so on.[2]

Sin in the Second City focus on the

local level, where many Progressives rallied to eliminate red-light districts

because prostitution was described as something that lured men “into awful sin

and death perhaps”.[3] The

reformers argued that prostitution perpetuated sin and death in many ways, but

the two arguments that stood out were health issues and also protecting the

sanctity of marriage. During the Progressive Era, there were many innovations in

science that helped address health hazards. “The study of social hygiene was

advancing rapidly; recently, a scientist had developed a test to detect Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that

cased syphilis”.[4] The advances

in science during that time made detecting health risks easier which in turn

brought to light the sexual health issues prostitution created. These facts

helped reformers’ case that prostitution was a serious problem where “men must

understand that harlots were responsible for more that 25 percent of surgical

operations on good women, for the blindness of hundreds of babies”.[5]

This is when health and living standards were addressed during that time and

how the business of prostitution can lead to many health risks for the city.

The

sanctity of marriage was also a factor for debate in the Progressive Era. At

the time, women began to have a voice as they rallied for equality in not only

voting, but for divorce, access to higher education, birth control, and so on.

They were convinced that it was their duty and responsibility to purify

American society.[6] Perhaps

their biggest concern is marriage and divorce. For example Grace Cunnings Shaw

Kennedy, the wife of a well-known wealthy man who was a regular at the

Everleigh Club, “would be filing for divorce soon”[7]

after her husband admitted to many affair and rendezvous with prostitutes. Mr.

Shaw Kennedy’s indiscretions cased a number of Mrs. Shaw Kennedy’s friends to

avoid their house, causing many strains on many relationships. Because of

situations like this, women reformers in the Progressive Era spoke out against

the negative effect prostitution have on traditional marriages, the family, and

most importantly the children affected by an unconventional family. Therefore,

divorce was also a hot topic in reforms.

Another

reform Progressives sought to eliminate was the corruption of government. For

example, “the first ward, the heart of Chicago’s culture and commerce, was

still run by the most crooked alderman. The police department still favored segregating

the Levee district rather than wiping it out altogether”.[8]

This to reformers was odd because even though there were many arrests of white

slave owners for disorderly conduct, there was still not an urgency to crack

down on the law. This is in part because of the corruption in government

because many government officials at the time made deals with leaders of red

light districts for their own political and financial gain.

|

| A portrait of Mona Marshall |

Another

important push of the Progressive Era is to Americanize immigrants or restrict

immigration all together.[11]

“In November 1907, the United States government, concerned about immigration in

general and its relationship to prostitution in particular, formed a commission

to study how people came to America and what happened to them once they

arrived”.[12]

Immigrants at the time were viewed as the main problem in the city’s

overpopulation and the advancement of while slavery. They were seen as

“mongrels, all of them, pulling America’s identity in dangerous directions

leaving her misshapen and newly strange”. Therefore, the federal immigration

Act of 1907 was implemented and agents began infiltrating red-light districts,

forbade importing women into the country for the purposes of prostitution, and

mandated he deportation of any woman or girl found prostitution herself within

three years of arriving to America.[13]

This made what use to be typical business in the Levee district now a felony.

This shows the influence of mass immigration and the relationship to

prostitution.

|

| Mina (Left) and Ada Everleigh |

Even

though prostitution in the text, especially in parts two and three, was mostly

shown as negative, Abbott still portrays the Everleigh sisters as heroines as

Ada and Minna were not vicious criminals like William McNamara, who “lured

girls and raped them, often several times, before selling them to brothels”.

The sisters made prostitution into a decent business and kept doctors to take

care of the harlots, paid the harlots well, and had strict rules against

violence, drugs and theft. Perhaps Abbott portrayed the sisters in such a

positive way to help the audience consider why prostitution was acceptable

during that time and it’s role in society and that prostitution can be like any

other business.

All

in all, Sin in the Second City accurately depicted the Progressive Era that

transformed American society in the 20th century, including mass

communication with newspapers and muckraking journalists, innovations in

science that helped health and living standards, the role of women in society, and

brought to light the role of government.

[1] Karen

Abbot, Sin in the Second City:

Madams, Ministers, Playboys and the Battle for America's Soul (New

York: Random House, 2007), 103.

[2] S.

Mintz, and S. McNeal. Digital History, "Overview of the Progressive

Era." Accessed March 31, 2014. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=11&smtid=1.

[4] Abbot, Sin in the Second City, 102.

[5] Abbot, Sin in the Second City, 102.

[6] S.

Mintz, and S. McNeal. Digital History, "Overview of the Progressive

Era." Accessed March 31, 2014. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=11&smtid=1.

[7] Abbot, Sin in the Second City, 105.

[8] Abbot, Sin in the Second City, 118.

[9] S.

Mintz, and S. McNeal. Digital History, "Overview of the Progressive

Era." Accessed March 31, 2014. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=11&smtid=1.

[10] Abbot, Sin in the Second City, 129.

[11] S.

Mintz, and S. McNeal. Digital History, "Overview of the Progressive

Era." Accessed March 31, 2014. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=11&smtid=1.

[12] Abbot, Sin in the Second City, 137.

[13] Abbot, Sin in the Second City, 154-155.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)